Prairie Restoration

The site: The company Heritage Seedlings has spent the last 16 years working on the Jefferson Farm Restoration just outside of Jefferson, Oregon. They hired botanist Lynda Boyer to be the overseer of the project. This is probably the largest private restoration project in the state; the project is working to enhance and restore 135 acres of habitat that was formerly grass farm and grazing pastures. Prior to 1850, much of the Willamette valley was open prairie and now there is only 1% left. I will link here a wonderful presentation that Lynda has posted on the heritage seedlings website that is full of good information in her own words.

The components of a native meadow:

There are two main things that make up a prairie: grass and forbes. Grasses used in restoration projects include Prairie Junegrass, Romer’s fescue, California Oatgrass and Pine Bluegrass. Forbes are essentially the perennials and annuals that come up every year. These include plants like Checker Mallow, Erigeron, Iris tenax, Camas, etc.

HERE is an article Lynda wrote in 2018 about pollinators; the whole thing is worth a read, but if you’re in a hurry she starts a list of desirable native forbes and grasses on page 49.

Getting started:

Lynda gave some very practical advice for how to get started on a site.

- You don’t have to start from scratch; let things come up and do an inventory of what is already thriving on your property—you might be surprised by what you find.

- If there are native plants present, collect seeds and plant them.

- Focus on getting rid of the invasive species that are present: rhizomatous grasses, blackberry, thistles, clover, etc. There are often certain herbicides that can be used to spot spray these plants.

- Keep in mind that as you take things out you are opening space for other options—have a plan for those possibilities! Otherwise, you may have just given breathing room for another invasive specie to take over.

- That being said, plant more plants! This can be done via seed, plants in plugs, pots or a combination. Lynda recommends planting grasses and forbes at the same time.

- Do you hate those gopher holes that pop up in your yard? Well now you can look at them as freshly disturbed soil that is there for the planting! Whenever the soil is disturbed in your site area, throw some seed in.

- Prior to 1850, a lot of the native prairie in the Willamette valley was maintained and cultivated by indigenous peoples through controlled burning. This helps control the invasives and encourages a lot of the forbes that propagate after fire. Controlled burning in this environment, for the average homeowner, is not a possibility. However, an annual mowing/string trimming will mimic the effects of the fire. It is best to mow as late in the fall as possible and leave the meadow at a 6” height. Depending on the site, you could even stretch it to mowing every other year in a patchwork pattern, helping the insect population who is at home there to thrive.

Potentilla with Spider

A word about pollinators:

Joining our tour was an entemologist who explained the very complicated system surrounding pollinating insects and plants. What bug pollinates which plant is completely variable based on location and year. Jefferson Farm provides an important space where he and his colleagues can observe and study the pollination habits of insects and our native plants over a long span of time.

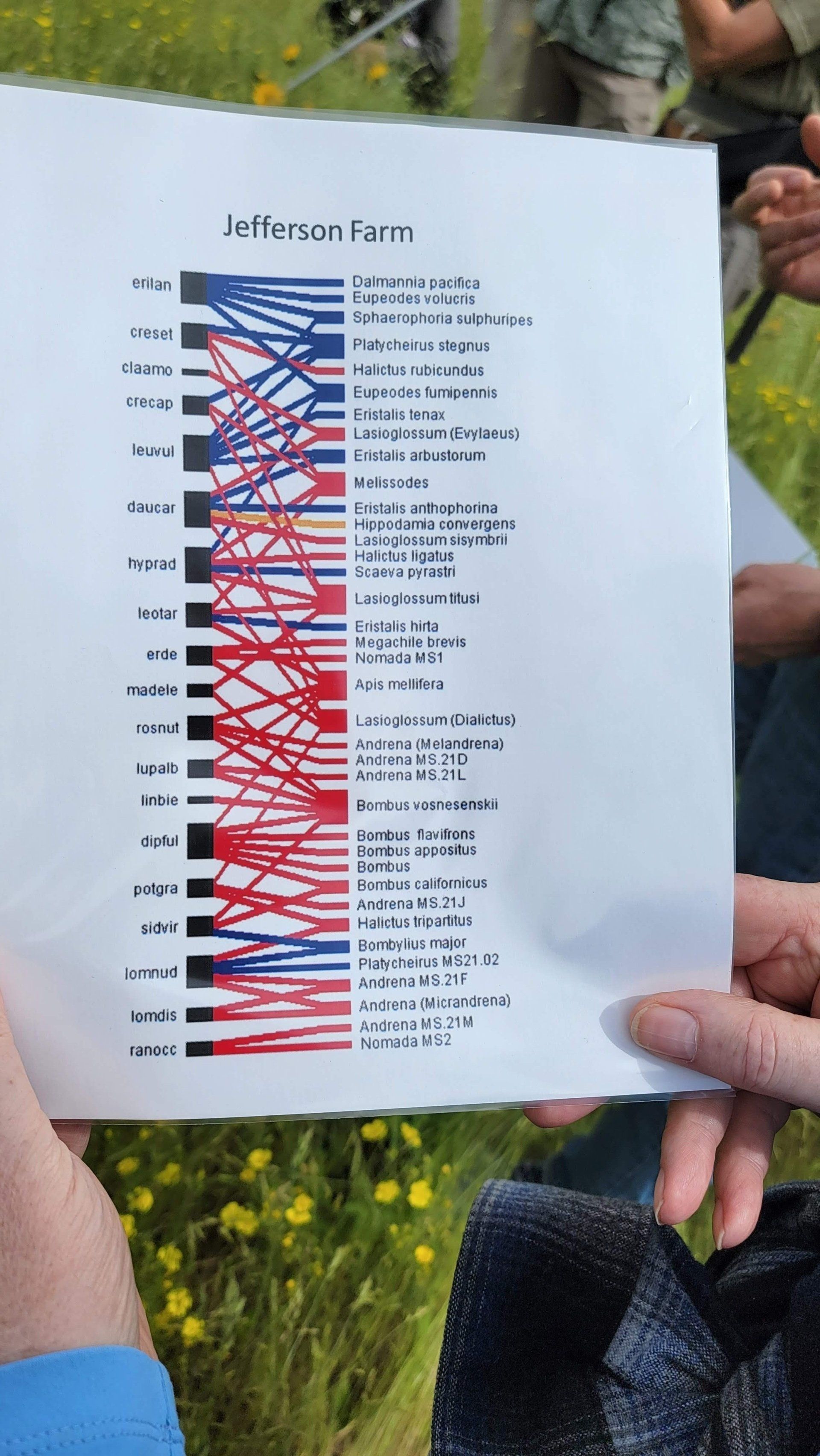

This is a list entemologists have made of the pollinators at Jefferson farms and the plants they visit. You can see how complex it is.

More and more I have clients who want to incorporate a piece of restoration onto their property. Here are some things I think clients need to know:

- You have to be comfortable with weeds; you will probably never 100% get rid of invasives, you simply have to control them as best as you can and pick your battles. For example, focus on killing the blackberries first over the oxeye daisies. Here is a poster of some of the worst invasives we have here in Oregon

- You will have some failures; you just have to keep trying things to see what takes, you cannot give up easily.

- It takes consistency to get it looking good.

- Start with a small area and increase it as you go so it doesn’t feel overwhelming all at once.

- There are some really smart people (like Lynda Boyer) doing this on a huge scale. If you’re passionate about this, see what they’re doing, if there are ways you can get involved and what information you can glean from what they have accomplished.

- Spring season is the season that shines. In our climate here in the valley, wild meadows will look their best and be at their peak in the spring when the majority of the forbes are blooming—a lot of our native perennials go dormant in the summer heat.